“ If God wills, when we return to our homes in Rafah—even though they’re destroyed—I’ll dance the dance of freedom amid the rubble.”

- Nahed AbouArmaneh

These are the words Nahed shared with me as I asked him about returning home. It is a sentiment that many Palestinians have shared with me as I have interviewed them and asked them why they are making the arduous journey back to Northern Gaza.

Nahed says life in Gaza has become about coming and going. Everyone’s mental faculties are reduced to calculations of survival. Once, Nahed occupied himself with dancing, writing, teaching, and harboring dreams—now he laments how war shrinks the existence of an entire people.

He has four children—Sara, Yara, Yousef, and Aboud—whom he has provided for through his work in telecommunications. Despite the scarcity of food, medicine, and other supplies, he continues to care for them. Being a father, he says, is the hardest role under these conditions, where even the simplest needs seem insurmountable.

Nahed’s former home was in Rafah, in a building that housed several of his siblings and their families. For several months, he was on the emergency telecommunications team, trying to restore network service amidst blackouts and helping the community as much as possible. There were initiatives for food parcels and personal hygiene supplies for displaced people in Rafah, and Nahed was an active volunteer.

For a time, life in Rafah was still livable for Nahed and his family even as destruction loomed. Nahed was doing comparatively well enough so that he opened his doors to those displaced from other parts of Gaza—people with nowhere else to go, fleeing death. But that relative protection was short-lived.

In May 2024, a missile fell on their building. The IDF’s perpetual destruction reached Nahed’s family, taking the life of his brother and tainting his children’s memories with the sight of their uncle’s death—something he says they will never forget.

There was no time to grieve, as survival became the only priority. They hastily buried his brother and had to seek safety. There is no space to mourn his loss or the loss of his deceased brother's family, because the quest for safety under the genocide leaves no time to be human. Their lives turned into a series of departures:

from Rafah to Khan Younis,

from Khan Younis to Deir al-Balah,

from Deir al-Balah back to Khan Younis, and so on. “A coming and going,” he calls it—a displacement that never settles.

Nahed is reluctant to discuss his hardships. Detailing the indignities of a life of scarcity is a sharper pain when you have a family—like needing to borrow a few pieces of bread for his children. When you are used to providing for your family, he says, asking neighbors for food can strike a blow to your sense of pride.

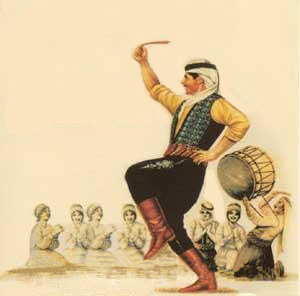

Nahed is happier sharing stories that remind him of better days—like the time his two young daughters performed Dabke side by side with him.

He recalls with warmth how they gleamed with joy watching their father perform on stage and how his pride grew, knowing his daughters were there to share in that moment. He learned the cultural dance of Dabke at just ten years old, performed on large stages throughout his life, and later taught it in community centers, passing on that devotion to his children. In the midst of conflict, dancing serves as a psychological weapon to fight for the preservation of the soul and the culture of a people oppressed and threatened with erasure for 76 years.

“The artistic ritual is in our blood,” he says, and no week goes by without engaging with the spirit of Dabke. He recounted a brief trip he made back to Rafah to see what was left of his home. The adornments and decorations that symbolize Palestinian Dabke—the photos and archives that cement memories and heritage—were lost. To his surprise, he found that his speaker was still intact and working, so he played Dabke songs with his family. However, that visit was brief, as his home lies on the Philadelphi corridor—a heavily militarized zone. Within a couple of hours, an IDF tank entered and began firing, yet Nahed managed to escape once again with his family without getting killed. While his escape attests to his and his family’s physical survival, retrieving the intact speaker symbolizes his spirit’s determination to remain alive.

When asked about the destruction of his home, the acknowledgment of every

other Palestinian’s similar loss restrains his grief and unites them in their suffering. To make some admission of that pain, Nahed cites the words of his friend Mahmoud Juda, a Gazan writer: “Our houses aren’t just stone. They are part of us—our flesh, our toil, our dreams. A house never truly returns once it’s gone, because it’s your entire life’s ambiance and fragrance. It’s so difficult to recreate.”

Part of the pain, he says, comes from the abrupt end to life’s routines. Where there was once schooling, work, and family gatherings, there is now a frantic search for water and safety. The comfort of a home has been replaced by the frailty of a tent that neither shields from the heat of summer nor the cold of winter.

Aid doesn’t always arrive where it should, either. Trucks bearing supplies may cross in, but distributing them fairly is strained with obstacles—roads are damaged and areas are restricted. Some families slip through the cracks. It pains him to see neighbors who can’t secure much of the necessities. The scarcity, deliberately designed to restrict food and aid from entering, has spiked prices to unfathomable levels. A kilogram of flour cost 500 dollars at one point.

There is an unspoken exhaustion that pervades his story. Where there used to be a struggle to make ambitions a reality, now his struggle is to fetch gallons of water and walk miles to get food. He and his family lost almost all their belongings, leaving behind not just clothes and memories, but a sense of stability and peace.

Though the life Nahed and his family lead is marked by restrictions on enjoyment and creativity—bereft of the simple necessities that a peaceful life takes for granted—his hope is steadfast. His story stands as a testament to finding meaning and freedom in what little is afforded, even when existence is constrained by external forces. Nahed’s resilience is not without pain but comes with an acceptance of pain intertwined with the will to continue with what he still has.

🙏❤️🤍